The Deception & Misconceptions Surrounding Boxing Videogames

These talking points didn’t come from data. They came from risk-avoidance, old metrics, and design shortcuts. And once you see that, a lot of modern boxing game decisions suddenly make sense, in the worst way.

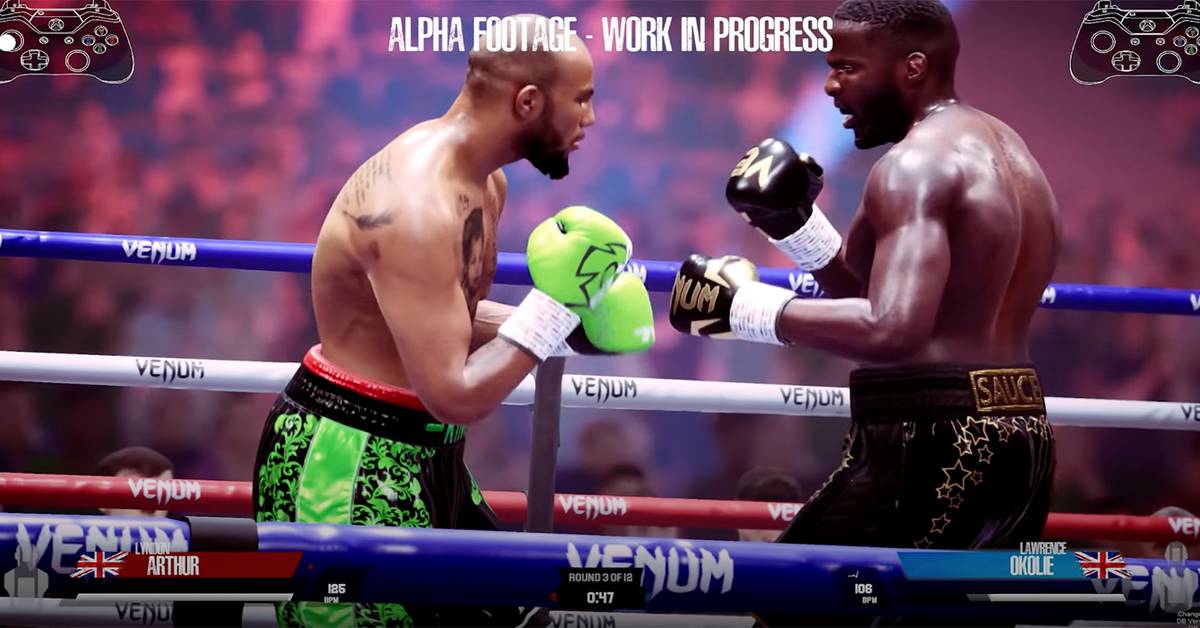

1. “Boxing games don’t sell well.”

This is not a genre problem. It’s a product problem.

What actually happened:

Boxing games stopped releasing regularly

Systems stagnated

Features were stripped, not expanded

Innovation slowed while expectations rose

A genre doesn’t “fail” when it disappears for a decade. It atrophies.

If boxing truly “didn’t sell,” you wouldn’t see:

Persistent demand across console generations

Boxing games are dominating YouTube view counts years after release

Communities are still dissecting mechanics from games released in 2004–2011

Fans begging for systems, not spectacle

What didn’t sell was:

Shallow mechanics

Limited offline depth

“Good enough” releases banking on nostalgia

2. “Casual players are the main audience.”

This is one of the most damaging misconceptions in sports gaming.

Here’s the sleight of hand:

Casual players are louder in metrics

Hardcore players are longer in retention

Casual players:

Drop in

Play briefly

Move on

Hardcore players:

Create boxers

Tune sliders

Play offline careers

Run leagues

Arguing mechanics for years

Buy DLC, sequels, and upgrades

Studios mistake visibility for value.

Retention, modding interest, offline playtime, and system mastery are what keep a sports title alive—not impulse purchases from people who bounce after two weeks.

3. “You need real boxers to sell.”

Licensing is a multiplier, not a foundation.

If real boxers were essential:

Historic boxing games without modern rosters wouldn’t be beloved

Created boxers wouldn’t dominate online and offline usage

Fictional fighters wouldn’t become community legends

What actually sells:

Identity ownership – creating your boxer

Style expression – seeing different boxers behave differently

Longevity – careers, legacies, what-ifs

Real boxers help marketing.

They do not replace mechanics.

A broken game with stars still breaks.

A deep game without stars still lasts.

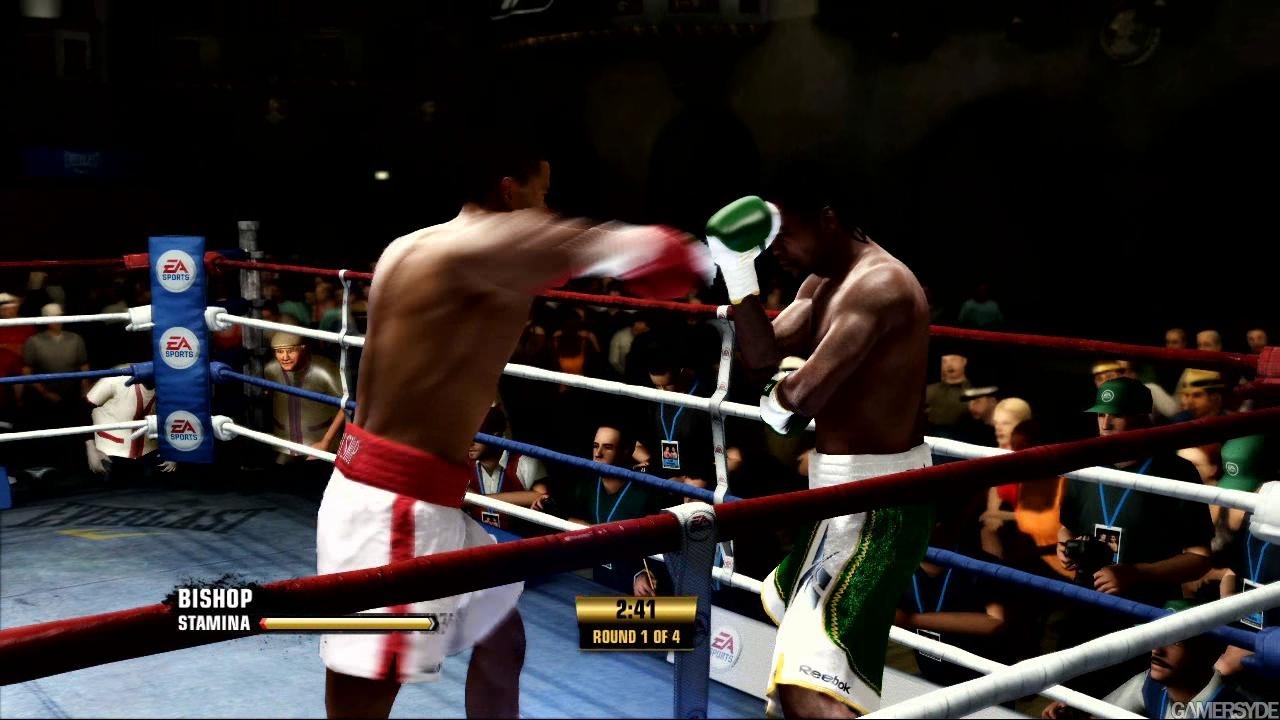

4. “Realism is slow (or boring).”

This one is pure misunderstanding.

Realism does not mean slow

Realism = consequence

Real boxing includes:

Explosive exchanges

Sudden momentum swings

Fast finishes

Tactical slow burns

Chaos and control existing together

What people actually mean when they say “slow”:

Inputs have recovery

Bad decisions get punished

Spam doesn’t work

Footwork matters

Distance matters

That’s not slowness.

That’s boxing.

The fastest fights in boxing history weren’t arcade—they were precise, risky, and decisive.

5. “Offline modes don’t matter anymore.”

This one is provably false just by behavior.

Offline players:

Spend more total hours

Use more systems

Explore more features

Care more about realism

Stick around longer

Online:

Is volatile

Is meta-driven

Suffers from balance compromises

Chases short-term engagement

Offline is where:

Career mode lives

Boxing fantasy lives

Experimentation happens

Long-term attachment forms

Killing offline depth doesn’t modernize a game; it shortens its lifespan.

6. The real reason these myths persist

Because they justify constraints.

They justify:

Smaller budgets

Fewer systems

Less AI depth

Fewer offline features

Avoiding complex mechanics

Not surveying players properly

They allow studios to say:

“This is the best we can do”

Instead of:

“This is what boxing actually demands”

The truth nobody likes saying out loud

Modern technology can absolutely support:

Deep realism and accessibility

Fast fights and consequence

Offline depth and online play

Created boxers and licensed stars

What’s missing isn’t capability.

Its intent.

The core takeaway

Boxing video games don’t fail because:

They’re realistic

They focus on offline

They prioritize depth

They respect boxing

They fail when they:

Chase outdated assumptions

Design for fear instead of fidelity

Confuse “casual-friendly” with “mechanically thin.”

Ignore the most invested players

I. Publisher / Investor Brief

Title: Debunking the Myths Holding Boxing Videogames Back

Executive Summary

The boxing videogame genre is constrained not by market demand, but by outdated assumptions about player behavior, realism, licensing, and offline play. These assumptions have led to risk-averse design decisions that actively suppress engagement, retention, and long-term revenue.

This brief outlines why those assumptions are incorrect—and how modern design approaches can unlock a sustainable, scalable boxing videogame market.

Key Misconceptions vs Reality

1. “Boxing games don’t sell well”

-

Reality: Boxing games suffer from irregular releases and underdeveloped systems, not lack of demand.

-

Evidence signals:

-

Persistent community engagement with decade-old titles

-

High creator-mode usage and offline playtime

-

Strong nostalgia retention across generations

-

2. “Casual players are the main audience”

-

Reality: Casual players are high in visibility, low in retention.

-

Long-term revenue is driven by:

-

Offline players

-

Career mode users

-

Customization-heavy players

-

System-focused players

-

3. “Real boxers are required to sell”

-

Reality: Licensing amplifies interest but does not sustain engagement.

-

Longevity comes from:

-

Player-created boxers

-

Style differentiation

-

Career narratives and legacy systems

-

4. “Realism is slow or boring”

-

Reality: Realism introduces consequence, not slowness.

-

Faster outcomes emerge naturally from:

-

Proper distance control

-

Punishable mistakes

-

Risk-based exchanges

-

5. “Offline modes don’t matter”

-

Reality: Offline modes produce:

-

Longer session times

-

Greater feature usage

-

Higher brand loyalty

-

Lower churn

-

Business Implication

Designing for realism, depth, and offline longevity does not reduce market size—it increases lifetime value per player.

II. Fan-Facing Manifesto

Title: Why Boxing Games Keep Missing the Mark

We’ve been told the same excuses for years:

-

“Boxing games don’t sell”

-

“Casuals are the main audience”

-

“You need real boxers”

-

“Realism is too slow”

-

“Offline doesn’t matter anymore”

None of that reflects how boxing fans actually play.

We don’t want faster buttons.

We want smarter systems.

We don’t want less realism.

We want better consequences.

We don’t want fewer modes.

We want meaningful ones.

A boxing game should let:

-

Styles clash

-

Mistakes matter

-

Careers unfold

-

Legends be built—not just licensed

This isn’t nostalgia.

It’s expectation catching up to technology.

III. Survey Questions (Accountability-Driven)

These are non-leading, data-forcing, and impossible to hand-wave.

Player Identity

-

How many boxing games have you played for more than 100 hours?

-

Which modes do you spend the most time in? (Offline Career / Online / Creation / Training / Other)

Realism vs Pace

-

Do you associate realism with slowness?

-

What matters more: animation speed or decision consequence?

Licensing

-

Would you buy a boxing game with no real boxers if the mechanics and career depth exceeded past titles?

-

How often do you play with created boxers vs licensed boxers?

Offline Value

-

Do offline modes increase how long you stay with a boxing game?

-

Would deeper offline systems increase your likelihood of buying sequels or DLC?

Retention

-

What keeps you playing long-term: mechanics depth, roster size, online ranking, or career immersion?

IV. Design Decision Mapping (Myth → Damage)

| Myth | Design Decision | Resulting Damage |

|---|---|---|

| Boxing doesn’t sell | Reduced budget & scope | Shallow systems |

| Casuals dominate | Simplified mechanics | Low retention |

| Need real boxers | Licensing-first focus | Weak gameplay |

| Realism is slow | Artificial speed-ups | Loss of authenticity |

| Offline doesn’t matter | Thin career modes | Short lifespan |

Final Takeaway (Unified)

The boxing videogame genre is not niche; it has been underserved.

Modern engines, AI systems, and data-driven design can support:

-

Realism and accessibility

-

Offline depth and online play

-

Created boxers and licensed stars

What’s been missing isn’t technology.

It’s honest intent and honest listening.

An Open Letter to the Boxing Videogame Industry

To the studios, publishers, investors, and decision-makers shaping the future of boxing games:

For years, boxing videogames have been held back—not by technology, not by fans, and not by lack of interest—but by a set of repeated assumptions that are treated as facts without being supported by meaningful data.

These assumptions have shaped budgets, features, pacing, and priorities. They have quietly dictated what boxing games are “allowed” to be.

It’s time to challenge them.

“Boxing games don’t sell well”

This claim is often stated as a conclusion, when it is actually the result of inconsistent releases, stripped-down systems, and creative risk avoidance.

Boxing did not disappear because fans lost interest. It disappeared because innovation stalled. The genre was allowed to stagnate while other sports titles evolved.

A genre does not fail because it goes quiet for a decade. It goes quiet because it is neglected.

The continued engagement with older boxing titles, the demand for deeper mechanics, and the persistence of online and offline communities prove that interest never left.

“Casual players are the primary audience”

Casual players are easy to measure because they appear briefly and in large numbers. That visibility is often mistaken for value.

But longevity comes from players who:

-

Create boxers

-

Play long offline careers

-

Tune sliders and systems

-

Debate mechanics years after release

These players are not casual. They are committed. They are the backbone of retention, community, and long-term revenue.

Designing primarily for short-term engagement sacrifices the players who keep a sports title alive.

“The game can’t sell without real boxers”

Licensing is a marketing tool—not a substitute for depth.

Players build their attachment through:

-

Custom boxers

-

Career arcs

-

Style expression

-

“What if” scenarios

A roster sells a trailer. Mechanics sell a legacy.

History has shown that players will invest hundreds of hours into fictional or created fighters if the systems allow identity, growth, and consequence.

“Realism is slow or boring”

This misconception confuses realism with hesitation.

Real boxing is not slow—it is deliberate, explosive, and unforgiving. Fights can end in seconds or unfold over tactical wars. What makes boxing compelling is not constant speed, but constant risk.

When realism is labeled “slow,” what is often being rejected is:

-

Recovery time

-

Punishment for mistakes

-

The inability to spam safely

-

The need to think before acting

That isn’t slowness. That’s accountability.

“Offline modes no longer matter”

Offline modes are where most players spend the majority of their time.

They are where:

-

Careers develop

-

Systems are learned

-

Styles are tested

-

Emotional attachment forms

Online play is important—but it is unstable, meta-driven, and often forces compromises that weaken authenticity.

A boxing game without strong offline depth does not modernize the genre. It shortens its lifespan.

The uncomfortable truth

These misconceptions persist because they make it easier to justify limitations.

They justify:

-

Reduced scope

-

Shallow AI

-

Simplified mechanics

-

Thin career modes

-

Avoidance of complex systems

They allow the industry to say, “This is the best we can do,” rather than, “This is what boxing demands.”

What fans are actually asking for

Not extremes. Not gatekeeping. Not nostalgia.

Fans are asking for:

-

Realism with options

-

Depth without exclusion

-

Speed with consequence

-

Offline longevity alongside online play

-

Systems that reflect how boxing actually works

Modern technology already supports this. Other sports genres have proven it repeatedly.

The barrier is not capability.

It is intent.

A call to action

Survey your audience transparently.

Stop speaking for boxing fans—start listening to them.

Design for longevity, not just launch metrics.

Boxing deserves the same respect given to other sports. So do the people who have supported it through decades of silence.

This is not a demand for perfection.

It is a request for honesty.

Respect the sport.

Respect the fans.

And let boxing games finally evolve.

.png)