Is Creating a Boxing Videogame Risky?

And Who’s Actually Responsible When It Fails?

There’s a lazy narrative that always appears when boxing games struggle:

“Boxing is niche.”

“Fans are unrealistic.”

“People expect too much.”

That narrative collapses under scrutiny.

Let’s break this down clearly.

1. Is Creating a Boxing Videogame Risky?

Market Risk vs Execution Risk

These are not the same thing.

Market Risk

Boxing is not a niche sport.

It has global sanctioning bodies.

It has Olympic presence.

It spans over a century of professional history.

It has cultural impact across continents.

Olympic Games

World Boxing Association

There have been over 100 boxing video games in some form across arcade, console, PC, and mobile. Genres don’t reach that count if there is no audience.

When modern boxing games appear, they get attention immediately:

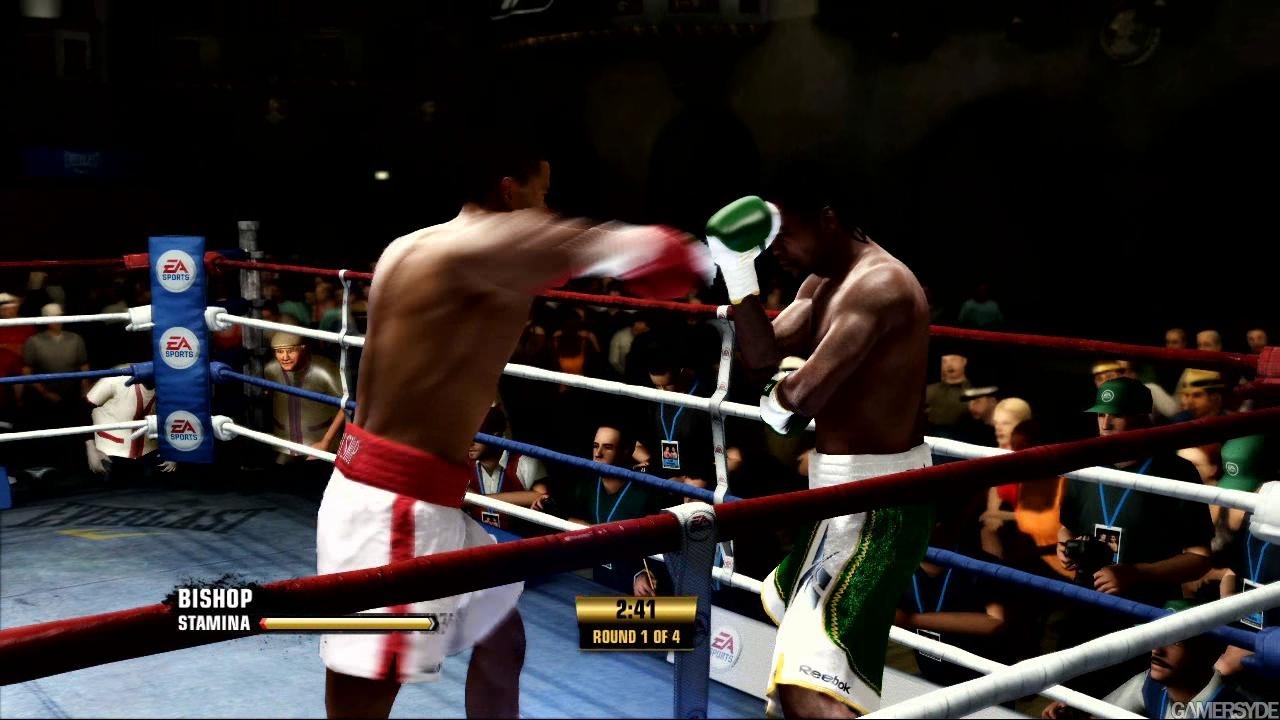

Fight Night Champion

Undisputed

That’s not niche behavior. That’s suppressed demand resurfacing.

So no — boxing itself is not inherently high-risk.

The Real Risk: Execution

Boxing is system-heavy.

A true simulation requires:

Footwork geometry

Punch physics and mass transfer

Defensive layers (slip, parry, shoulder roll, block)

Scoring nuance

Damage modeling

Referee logic

Clinch systems

Ring IQ AI

If a studio markets “realistic” and ships arcade foundations, players who understand boxing will detect it quickly.

That’s not toxicity.

That’s pattern recognition.

The biggest risk in boxing game development is expectation misalignment — not audience size.

2. Is Investing in a Boxing Game Risky?

From an investor perspective, the questions are different.

Not:

“Do fans love boxing?”

But:

“Is this scalable and repeatable?”

Here’s the honest breakdown:

| Factor | Risk Level |

|---|---|

| Licensing complexity | High |

| Mocap and animation depth | High |

| AI engineering requirements | High |

| Global appeal | Strong |

| AAA competition | Low |

Notice something important.

There is very little direct AAA competition in boxing gaming right now. That lowers competitive pressure.

The financial risk isn’t the sport.

It’s underestimating development depth and overselling capability.

3. What Steel City Interactive Demonstrated

Steel City Interactive proved something crucial:

Fans will:

Buy early.

Debate mechanics intensely.

Support a realistic direction long term.

Stay if they feel respected.

But they will leave quickly if:

Marketing overpromises.

Language shifts from “realistic” to “authentic.”

Core systems feel shallow.

Communication disappears.

That isn’t niche fragility.

That’s trust erosion.

4. Who’s at Fault When Dissatisfaction Happens?

This is where studios need to look internally instead of outward.

When fans say:

“The representation isn’t deep enough.”

The wrong response is:

“Fans are impatient.”

Because fans do not:

Decide staffing levels.

Write marketing copy.

Allocate AI budgets.

Control engineering scope.

They respond to what they were sold.

If a game is promoted as:

Hyper realistic

Like chess, not checkers

Made by boxing fans for boxing fans

Then expectations were created internally.

If delivery does not match positioning, dissatisfaction is a predictable outcome — not community sabotage.

5. Internal Questions Companies Should Be Asking

Instead of framing frustration as a fan problem, studios should ask:

Was the AI team large enough for a systems-driven sport?

Was marketing aligned with engineering reality?

Was scope controlled properly?

Were core mechanics prioritized over cosmetics and licensing?

Was communication transparent during instability?

These are leadership questions.

Not community flaws.

6. Representation Is Not Cosmetic

Boxing fans are not asking for surface features.

They’re asking for:

Real stamina management.

Real defensive diversity.

Real boxer individuality.

Real scoring nuance.

Real ring craft behavior.

That’s not entitlement.

That’s the sport.

When representation is shallow, it feels like boxing is used as a theme instead of being built as a system.

And when companies blame fans for pointing that out, they damage long-term brand equity.

7. The Corporate Reflex That Creates More Risk

Blaming fans does three dangerous things:

It erodes trust.

It scares investors more than criticism ever would.

It shrinks lifetime value.

Because once trust is broken, players hesitate before buying the sequel.

That’s where the real financial risk lives.

Not in boxing.

In credibility.

8. The Honest Conclusion

Creating a boxing videogame is:

Technically demanding.

Resource heavy.

Strategically viable.

Not inherently high-risk if properly staffed and honestly marketed.

Investing in one becomes risky only when:

Marketing outpaces engineering.

Internal audits are replaced by external blame.

Representation is treated as optional depth instead of foundational design.

Boxing is not niche.

Poor execution is.

And dissatisfied fans are not the cause of failure.

They are the early warning system.

If companies want lower risk, they should not lower expectations.

They should raise internal alignment.

Boxing Game Sequel Greenlight Post-Mortem Template

Internal Use Only – Leadership, Production, Design, Engineering, Publishing

I. Core Question

Did the first game fail because of the market… or because of us?

No sequel should move forward until this is answered with brutal honesty.

II. Market Reality Audit

1. Sales Analysis

-

Total units sold (lifetime)

-

Sales in first 30 / 60 / 90 days

-

Retention curve at:

-

1 week

-

1 month

-

3 months

-

6 months

-

-

DLC attach rate

-

Price drop impact on sales

Key Question:

Did players leave because boxing is niche, or because trust eroded?

2. Sentiment Analysis (Not Cherry-Picked)

Analyze:

-

Steam reviews

-

Console reviews

-

Discord discussions

-

Social media feedback

-

YouTube breakdowns

Separate feedback into categories:

| Category | % of Mentions |

|---|---|

| AI depth complaints | |

| Gameplay realism complaints | |

| Bugs/performance | |

| Lack of options | |

| Communication frustration |

If “lack of representation depth” is high, that’s a systems issue, not a market issue.

III. Systems Audit (The Hard Part)

1. AI Architecture Review

Was the AI:

-

Behavior tree based?

-

State machine limited?

-

Data-driven?

-

Modular?

Did it support:

-

Ring generalship?

-

Adaptive tactics?

-

Fatigue-based decision changes?

-

Style individuality?

If the AI was reactive but not strategic, you did not build a sim foundation.

2. Combat System Depth

Was combat:

-

Animation-driven with logic layered on?

-

Or logic-driven with animation supporting it?

Was there:

-

True mass transfer modeling?

-

Foot placement affecting punch outcome?

-

Defensive reads beyond timing windows?

If not, you built presentation first, simulation second.

That matters.

3. Representation Integrity Check

Ask directly:

Did the game simulate:

-

Scoring nuance?

-

Ring control?

-

Pace management?

-

Clinch battles?

-

Damage accumulation realistically?

Or did it simulate:

-

Flash knockdowns

-

Highlight reactions

-

Surface authenticity

Be honest here. This determines sequel viability.

IV. Production and Staffing Review

1. AI Staffing

How many engineers were assigned to:

-

AI logic

-

Systems tuning

-

Combat balancing

Compare that to:

-

Animation team size

-

Art team size

-

Marketing team size

If AI staffing was minimal compared to visual departments, the priorities were misaligned.

2. Scope Discipline

Did the team:

-

Secure too many licensed boxers early?

-

Spend too much time on presentation?

-

Overcommit on roadmap features?

Was core gameplay 100% stable before DLC production began?

If not, you created structural fragility.

V. Marketing vs Reality Alignment

List every major marketing claim.

Then mark:

-

Delivered

-

Partially delivered

-

Not delivered

If language evolved mid-cycle from:

“Realistic simulation”

to

“Authentic boxing experience”

That shift needs to be explained internally before a sequel is pitched externally.

Marketing inflation creates sequel resistance.

VI. Communication Review

When the game hit turbulence:

-

Did leadership communicate clearly?

-

Did developers go silent?

-

Were updates predictable?

-

Was criticism addressed or dismissed?

Silence multiplies risk.

Defensiveness accelerates it.

VII. Financial Viability Model for Sequel

Before greenlighting:

A. What must be rebuilt from scratch?

-

AI core?

-

Animation graph?

-

Physics?

-

Networking?

B. What must be expanded?

-

Tendency systems?

-

Scoring logic?

-

Career mode depth?

C. Budget Reality

If the sequel requires:

-

Double the AI team

-

Rebuilt combat core

-

Extended QA cycle

Is leadership willing to invest that?

If not, do not greenlight.

VIII. Community Trust Index

Score from 1–10:

-

Trust in marketing

-

Trust in patch promises

-

Trust in realism claims

If average score is below 6, a sequel must include:

-

Transparent development diaries

-

Public systems deep dives

-

Honest feature scope communication

Without rebuilding trust, sequel sales will frontload and collapse.

IX. The Final Gate Question

Only greenlight a sequel if leadership can answer:

-

We understand exactly why players were dissatisfied.

-

We are willing to increase engineering investment.

-

We will not overmarket.

-

We will build systems first, spectacle second.

-

We are prepared for long-term support, not quick DLC cycles.

If any of those are shaky, a sequel increases risk instead of reducing it.

X. The Executive Reality Check

Boxing games don’t fail because boxing is niche.

They fail because:

-

Systems weren’t deep enough.

-

Expectations weren’t managed honestly.

-

Internal audits weren’t run before public promises.

A sequel should not be a second attempt at marketing.

It should be a correction of architecture.

No comments:

Post a Comment